Crim: As ‘one of the good guys,’ Heller impacted lives of thousands of athletes as player, coach and official

LAGRANGE, Mo. — Joe Heller remembers what Saturdays during basketball season were like growing up.

His mom, Carol, would pack the referee bag for his dad, Ed. Five separate changes of clothes were available, each change neatly packed together so Ed could just pull out the next set at each stop.

“He was stuck babysitting me, so I would ride with him,” said Joe, the youngest of Ed and Carol’s three kids.

“We would leave in the morning, and he would go referee boys and girls eighth grade games at Highland. Then we might head to Iowa or Illinois, and he would do two high school games. I knew it was going to be a good night if the last game was at Quincy College or Hannibal-LaGrange, because that meant I was going to get a milkshake.

“You never knew where he might end up refereeing. He would hit those schools, get his clothes on and get ready to go. He would referee four full basketball games and was still running with those college gazelles, never missing a step. And he knew everybody, everywhere.”

Ed Heller passed away Dec. 13 at 87, leaving a void his family is struggling to fill. Yet, he leaves behind a legacy of a man who devoted so much time to others and left an indelible mark on many, especially when it came to athletics.

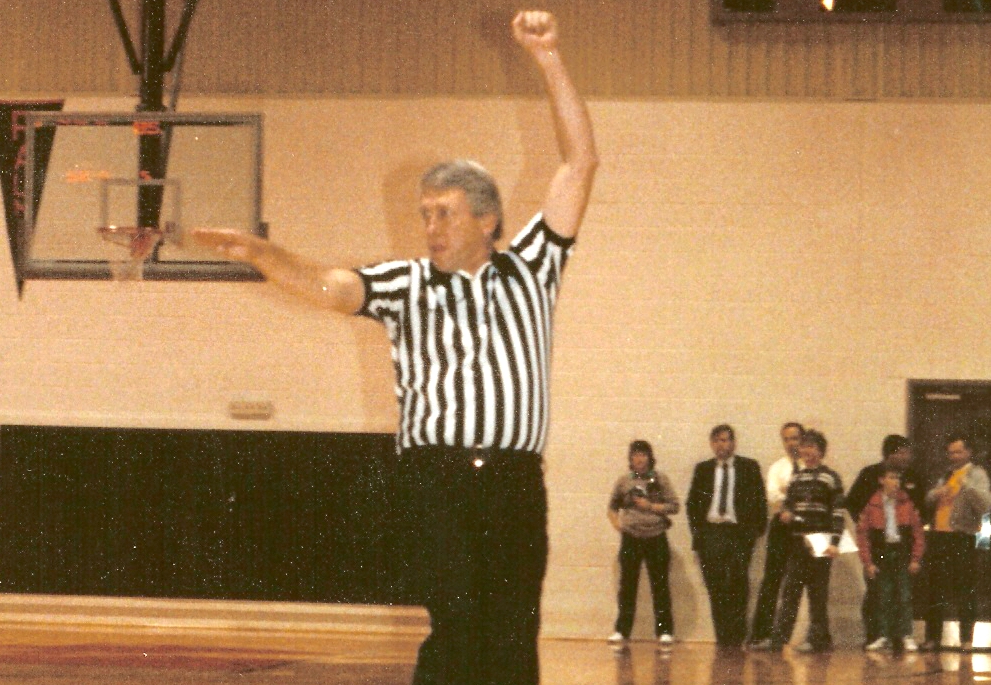

Heller officiated more than 5,100 basketball games

Ed was a fixture in high school and college gymnasiums, officiating more than 5,100 basketball games from 1962 to 1993, primarily in Northeast Missouri and West-Central Illinois. He called 11 girls state tournaments and was inducted into the Missouri Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2006.

You also could find him either behind the plate or working the bases for high school and college baseball and softball games for more than three decades. He spent 15 years as either an assistant or head coach with the Culver-Stockton College softball program.

“He called junior high games because people would call him up, and he couldn’t say no,” former Culver-Stockton men’s basketball coach Rod Walton said. “He always wanted to help somebody out. He would have done it, paid or not, because he enjoyed it so much.”

Nothing, it seemed, could keep him from calling games. Joe, then in college, remembers getting a phone call from his father one snowy, wintry day.

“He always drove an orange, straight-shift pickup truck. He was driving out to do games at the Highland Tournament, and everybody knows he never drove fast,” Joe said. “He calls me. ‘I rolled the truck. I’m close to Ewing. I’m in a ditch and need you to come get me out.’

“I get some buddies, and we get there and it’s not just in a ditch, it’s upside down and the windshield is busted out. We found out later that he broke two ribs, but he couldn’t miss a game. He refereed like nothing had happened.

“The funniest part is that dad was a die-hard Nebraska fan. He had a clip on the truck’s visor that would play the Nebraska fight song. After he got home and we were patching him up, he said, ‘You know Joe, when I rolled, I went out a bit. When I came back around all I could hear was There is No Place Like Nebraska.’

“He thought he had died and gone to heaven.”

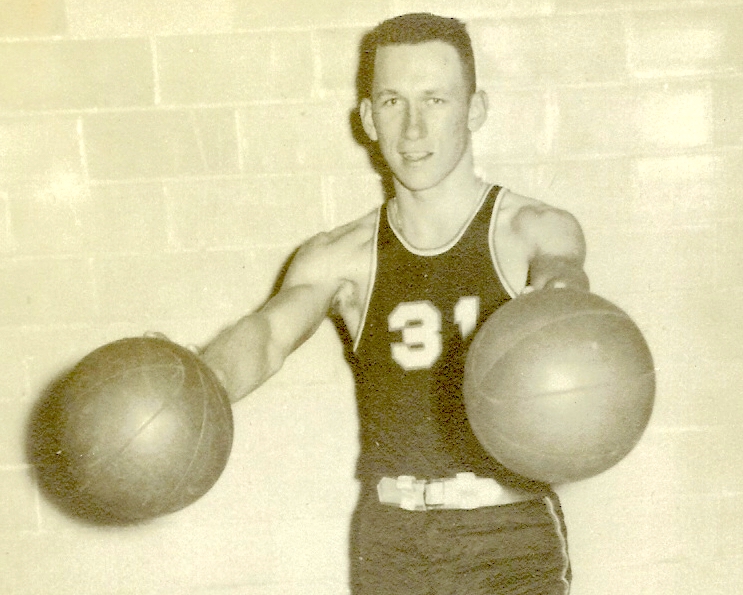

Grew up in Nebraska as standout in basketball, baseball

Ed was a standout high school basketball and baseball player growing up in Clatonia, Neb. He played on the freshman basketball team at the University of Nebraska, where he earned a degree before embarking on a 33-year career with the Soil Conservation Service.

For many years he was the player-coach on the Ozark Nationals, a fast-pitch softball team that featured legendary local pitchers Dick Thompson and John Stutsman.

“That’s where he seemed happiest, with that softball team,” Joe said. “They traveled all over the place.

“He had the greatest respect for Dick Thompson and his wife. He would tell me to watch how they reacted to a situation and feel free to copy it. To my dad, words didn’t matter that much. He said it was actions and behaviors that define you.”

At 6-foot-4 and 240 pounds, Ed cut an imposing figure on the court or the diamond, but he was anything but grandiose. He took his work seriously but not himself. He had an easy, outgoing personality that could diffuse tense situations.

“He had the correct temperament to be an official,” said Gene Hall, who worked alongside Ed in the 1980s and later, as the Culver-Stockton athletic director, hired him as a softball coach.

“When things got tight, he could loosen up the game and make it enjoyable. If you ever needed anybody to pump you up, loosen you up or tell a joke, call Ed Heller. He never met a stranger. Once you were introduced to him, you just let him do the talking.”

‘You don’t see any characters like him anymore’

Jim Ross, senior vice president at Peoples Bank & Trust in Louisiana, knew of Ed as a basketball official when he played in high school. Ed later took him under his wing when Ross began officiating.

“He had a disposition on the floor unlike most officials,” Ross said. “He could flash that wry smile or goofy look and settle things down. A coach might be getting all over him. and he would go over and say something goofy or funny like ‘Your tie is crooked,’ or ‘Your pants are unzipped.’

“He had a pocket full of jokes all the time. He was one of the good guys. You look at officiating today, and you don’t see characters like him anymore. Most are out for the money and not the game and the kids.”

Those traits carried over when he coached his kids in youth sports and when he was involved with the Culver-Stockton program.

“He coached my baseball team from the time I was 6 until I was 16,” Joe said. “The best advice he ever gave me as a coach was that every time you make a decision that affects a ballplayer, make a decision based on what that means to the kid the next year. The game is not important; the kid is.”

Aron Potter, now the vice president for academic services at Coffeyville (Kan.) Community College, played softball for Ed at Culver-Stockton from 1994-97.

She was a three-time All-Heart of America Athletic Conference selection, the league’s player of the year as a junior and helped the Wildcats win two conference titles and twice advance to the NAIA tournament. She later coached with Ed on college teams that toured Europe and Australia as part of a program promoting athletics and education.

“He was still a dirt bum out there with a rake, laying sod, pulling water hoses,” Potter said. “He could make an infield slow if you needed it slow, or fast if you needed it fast. He would then brush off his pants and go coach third base.

“He was what we would now call old school. He was very laid back. He trusted the players’ instincts and let us do what we did best. He wasn’t about the fancy stuff you see today. He put his hand in his pocket to indicate a changeup because that’s where he kept his change.”

Boxes of clippings, mementos, awards

The players witnessed another side to Ed.

“He was always about volunteerism and being part of your community, he and Carol both,” Potter said. “They were about service. Young coaches could learn from them. Being an active part of a community is something that is going to the wayside today.”

Joe and his siblings, Cindy and Chris, are finding out just how involved their parents were in the community as they go through boxes and boxes of newspaper clippings and other mementos in the family home.

“There are more awards and commendations, letters from senators and governors and keys to the city,” Joe said. “We never knew about any of this. He never talked about it. I didn’t know he was inducted into the hall of fame until I saw a story in the paper, and there was a picture of my dad. I remember finding boxes of plaques once in his garage and asking him about it. He said plaques are just dust collectors, that doing what it took to get them is what is important.

“It’s overwhelming the things this guy did and never told anybody. It seems like he has touched so many lives in so many ways. I never thought about it that way. He was just our dad.”

Ed Heller rarely drove past a ballpark or football field without stopping if the lights were on. He never passed up a serving of strawberry ice cream. He didn’t think anyone should “burn daylight when work should be done,” so he kept finding things to do despite retiring six times.

Above all, he always put his family first and tried to be an example for them to follow.

“The best thing you can say about Ed,” Walton emphasized, “is that he was a good man.”

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.