Crim: Stories of life well lived are gifts Gott gave to all who knew him

QUINCY — For many years, one of the benefits of being a member of Cedar Crest Country Club was the opportunity to sit around the patio either before or after a round of golf listening to Tom Gott tell stories.

“Stop me if I’ve told you this before,” he would caution before launching into a tale about growing up poor in Springfield, Mo., or about playing alongside Mickey Mantle in the minor leagues, or about some club members he may have swatted years before while dean of students at Quincy Junior High School.

No topic was off limits.

Many of us had heard the stories, of course, because Tom was always sharing them with either a chaw of Red Man in his cheek or a cigar in hand. We rarely stopped him, though. He was the club’s patriarch, after all, and too damn nice and enjoyable to be around to muzzle, especially if you were a baseball fan.

Tom passed away on New Year’s Day at the age of 94.

Unless off on a gambling excursion with his son, Kel, or tending to his wife, Rose, he was a fixture in our golf games and at the card table in the clubhouse until shortly before his 92nd birthday, when he was suddenly struck down by infirmities.

The place hasn’t really been the same since.

Most people in Quincy will remember Tom as a teacher and administrator in the city’s public and private schools. He was a firm, yet supportive educator. Whether it was providing extra help to students who needed it or straightening out those who crossed the line, his goal was to provide an environment where kids would have the opportunity to be the best they could be.

And he did that well.

His first career was in professional baseball, however.

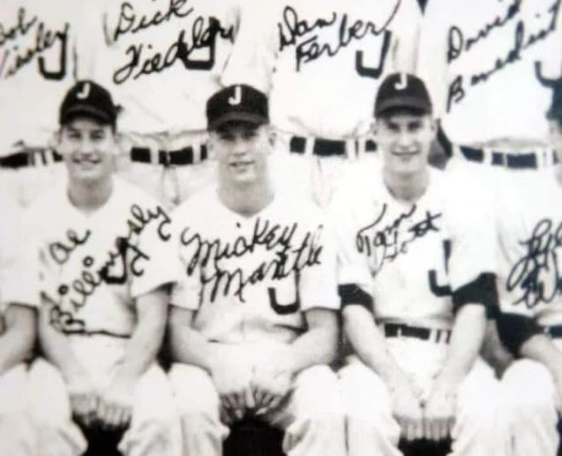

An outfielder, he signed with the New York Yankees out of high school in 1948. He was promoted to the Joplin (Mo.) Miners, the Yankees’ Class C affiliate in the Western Association, two years later. His roommate was an 18-year-old shortstop who later was converted to outfielder from Commerce, Okla. His name was Mickey Mantle.

Oh, did Tom love to tell Mickey Mantle stories. And we loved to listen.

“If you drew it up on paper, (Mantle) was the perfect athlete,” Gott said in a 2016 interview with David Adam, then with the Quincy Herald-Whig. “I mean he could just fly. … He was amazing. He had no idea how gifted he was. He would have been another (Lou) Gehrig if he hadn’t gotten on the booze.

“By the middle of the year (in 1950), everybody knew (how good Mantle was going to be). We’d take batting practice, and you’re in the outfield shagging balls. You could tell when Mantle was hitting because the ball was always on you quicker.”

A year later, Mantle was roaming the outfield for the Yankees in the World Series, the heir apparent to the retiring Joe DiMaggio, the start to a Hall of Fame career that spanned 18 seasons. His 536 career home runs trailed only Babe Ruth, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron when he retired on the eve of the 1969 season.

“(Mantle) was a special person in my book,” Gott told Adam. “We had so much fun doing stuff. Everything we did was clean fun. We never did anything we shouldn’t do, but we were always doing something. … He was competitive and fun-loving, like we all were.”

The Korean War interrupted Gott’s career. He returned in 1953 with the Quincy Gems, the Yankees’ Class B affiliate in the Three-I League. He led the league in hitting with a .348 average in 1954, but said he realized he was never going to make the major leagues, at least not with the Yankees.

“I didn’t hit home runs, and if you didn’t hit home runs and played the outfield, you didn’t go,” he told Adam. “There were all kinds of guys ahead of me. I was a double, triples, singles hitter.

“The best thing that happened to me was that I met my wife (in Quincy).”

With Rose and two kids in tow, Tom returned to Springfield to go to school and get a degree, which he completed in three years. The Yankees’ scout who signed him, the legendary Tom Greenwade, called in 1957 to see if Gott was interested in managing.

“I’m in debt and I’m not going to get that kind of money doing anything else, so I took it,” Tom said in the 2016 interview.

Still in his 20s, he spent one season as a part-time player and manager in the low minor leagues in Greenville, Texas, and another in Auburn, N.Y. In his final season, he was introduced to Joe Pepitone, a bonus baby who never realized his potential in a 12-year career with the Yankees, Astros, Cubs and Braves.

“He had all the tools,” Gott told Adam. “But God almighty, what a ding dong. We made it through the year with him, but he was something else.”

There was the story of Peptone stepping out of a New York City taxicab with his mother in reporting to Auburn. Another of a teammate finding Pepitone sitting in a bathtub with fish swimming around him. And then the first baseman sprayed a fire extinguisher in a hotel hallway, bleaching out the rugs.

“You can’t raise a family in baseball, so I got out after two years,” said Gott, then with three kids and another on the way.

He settled into a career in education in Quincy, eventually rising to associate superintendent of Quincy Public Schools. He later served as director of the Head Start program and as principal of St. Francis School. His accomplishments were many.

He had a keen love for kids, and it showed at Cedar Crest, too. He would buy candy for any youngster who showed up in the clubhouse with a parent or grandparent. He did it, he explained, “because I didn’t have any money to buy candy when I was a kid.”

In retirement, Tom could be found almost daily at Cedar Crest, usually arriving early for the customary noon game. He would light up a cigar — Rose wouldn’t let him smoke at home, he said — and sit on the patio, waiting for other golfers to arrive. And at the stroke of noon, he wanted to be headed to the first tee box.

He wasn’t a fan of the sometimes-slow pace of the game. If it was your turn, he would urge you to “go ahead and hit.” And there were many 6-foot putts playing partners were lining up that he would call good — “that’s a gimme” — so the group could move on to the next hole.

Tom wanted to get to the clubhouse as quickly as he could, so he could play cards with whoever wanted to join him until it was time to go home for dinner with Rose. Through it all, he would joke, order a round of drinks, discuss events of the day and spin tales, while usually coming out ahead on the bets.

Fun-loving, competitive and a gentleman, with hundreds of interesting stories to share.

If you drew it up on paper, Tom Gott was one of the best.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.