Crim: Saying so long to baseball’s all-time greats cannot diminish memories they helped create

QUINCY — For men of a certain age — I was born 10 days before Don Larsen threw the only perfect game in World Series history — the death of Willie Mays means another link to our youth is gone.

Baseball was the national pastime for kids growing up in the 1960s. While we knew the Green Bay Packers were the dominant team of the decade in the NFL and the Celtics were winning title after title in the NBA, it was baseball that we held dear.

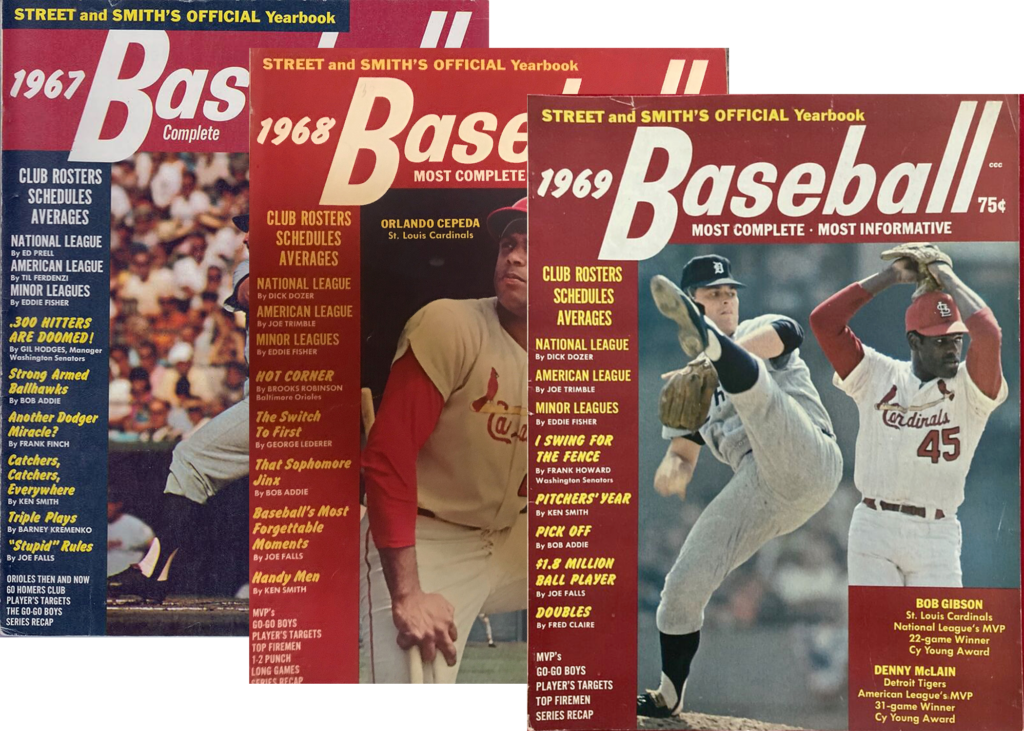

We bought Street and Smith’s Baseball Yearbook each spring to read the season preview of each team and scour rosters. We would flip to the back of the magazine to see where active players stood on the lifetime lists for home runs, hits, RBI, strikeouts, shutouts and games won, and recite them when necessary.

We would devour The Sporting News, a weekly newspaper broadsheet described as “the bible of baseball.” There were feature stories, minor league reports, box scores and columns — “Stove League Stories,” “Caught on the Fly,” “In the Bullpen.” We were introduced to legendary sportswriters like Dick Young, Bob Addie, Jerome Holtzman, Bob Broeg and Joe Falls.

There were gobs of magazines on grocery store shelves to choose from — Sports Illustrated, Sport, Baseball Digest being the most prominent — and we’d beg our parents to shell out an extra 50 cents and add it to the shopping cart.

We would go to the local dime store to buy 10-packs of Topps baseball cards with our lawn mowing money in hopes of unwrapping our favorite players. We memorized the statistics on the back and used them for neighborhood pickup games while we mimicked pitching motions and hitting stances as we played.

Luis Tiant on the mound or Willie Stargell preparing to hit, anyone?

We would tune in to NBC’s Game of the Week each Saturday afternoon with Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek. National games also would be televised on Memorial Day, Independence Day and Labor Day, and, of course, the All-Star Game (when winning was a matter of pride) and the World Series.

Mostly, though, we would tune in our favorite teams on our transistor radio. For those of us growing up in Missouri, it was Harry Caray and Jack Buck calling the Cardinals. Every now and then on a clear summer night we might be able to pick up Ernie Harwell in Detroit or Bob Prince in Pittsburgh.

A friend once aptly described it: Football is an event; baseball is a companion.

Stars were in abundance in the 1960s.

ESPN’s all-decade team consisted of Joe Torre catching, Harmon Killebrew at first base (narrowly edging out Willie McCovey), Pete Rose at second, Brooks Robinson at third and Maury Wills (primarily because he stole a then-record 104 bases in 1962) at short.

The outfield was manned by Mays, Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente, with Frank Robinson as a utility player. The starting pitchers were Sandy Koufax, Juan Marichal, Bob Gibson, Don Drysdale and Jim Bunning, with Hoyt Wilhelm in relief.

Only Rose and Wills aren’t in the Hall of Fame, and Rose, the all-time hits leader, would be enshrined had he not been banned for betting on baseball as a manager. Torre later made it as a skipper.

Sadly, we’re losing our connections to that era at an alarming rate.

McCovey passed away in 2018 and Frank Robinson the following year. In 2020 we lost Gibson, Lou Brock, Dick Allen, Al Kaline and Tom Seaver. Aaron died in 2021. Two other key players on the 1960s Cardinals — Tim McCarver and Mike Shannon — left us in 2023.

And now Mays. Father Time remains undefeated.

Luis Aparicio is now the oldest living Hall of Famer at age 90. Koufax is 88, Bill Mazeroski is 87 and Marichal, Orlando Cepeda and Billy Williams are all 86.

There’s a new generation of baseball stars today. While it’s true they’re better athletes, I can’t say the game is better.

There’s too much emphasis on launch angles and home runs, the stolen base is a forgotten art, and pitchers are applauded for “quality starts” if they go six innings while giving up three runs or fewer.

Koufax, by comparison, threw more than 300 innings in each of his final two seasons with an arthritic elbow and posted a combined record of 53-17 with 699 strikeouts and an ERA below 2.00. Fifty-four of those were complete games.

In 1968, Gibson started 34 games, completed 28, allowed just 38 earned runs in 304.2 innings pitched and tossed 13 shutouts. He was so dominant that baseball lowered the mound after that season to give hitters a chance.

We won’t see their likes again.

Maybe there will be another five-tool player like Mays, a whirling dervish with a rocket arm like Clemente or a majestic swing like Aaron’s. A few have since staked their claim to greatness, certainly. It’s the nature of baseball, one era begetting another, always chasing records and history.

For those of us who grew up in the 1960s, however, it was those players who made us fall in love with the game, their greatness unchallenged.

While many of them are gone now, the memories they created remain.

That, too, is one of the beauties of baseball.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.