Crim: From Warsaw to West Point to the world, Rothert’s journey is fascinating tale

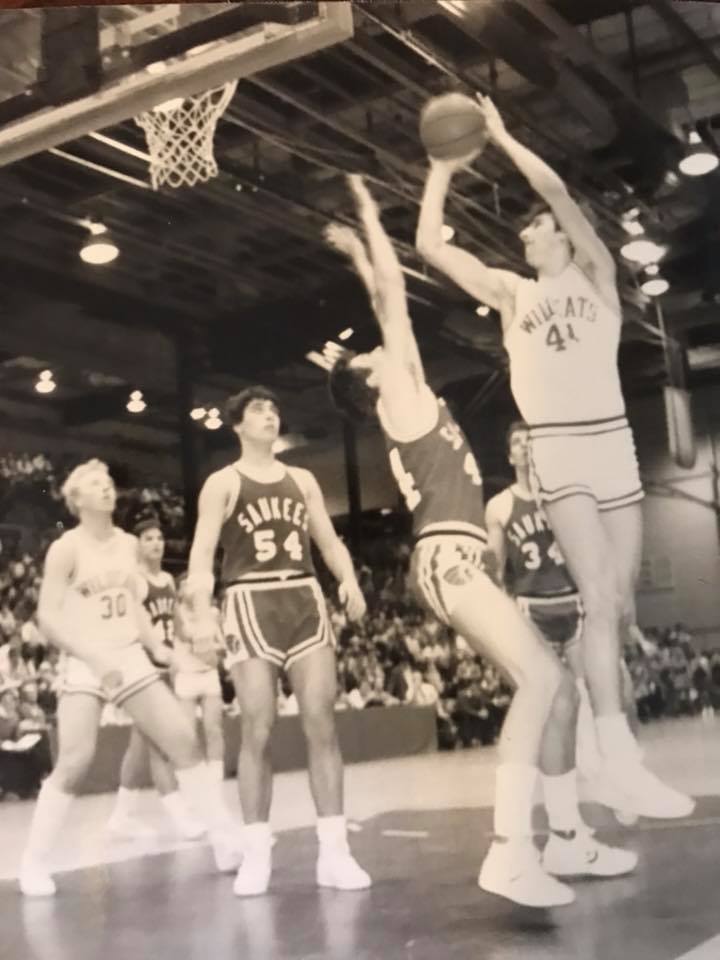

ANKARA, Turkey — Steve Rothert was preparing to play for the Illinois All-Stars in the 1986 McDonald’s/Herald-Whig Classic when we sat down to discuss his all-state basketball career at Warsaw High School and appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The essence of the column I wrote then was that Rothert was a model citizen on and off the court, a high school athlete who made headlines on the sports pages while also starring in the classroom. If that wasn’t enough to admire, I concluded, he was one of the nicest guys you would ever want to meet.

“When I look back on high school,” he told me that day, “I think everything has gone right. I don’t know of anything that I would change if I could. I hope it is a harbinger of things to come.”

It was a prelude, all right, of a life even Rothert could not have imagined.

• He played against David Robinson, Lionel Simmons and Christian Laettner — all future first-round NBA draft selections — during his four seasons at Army. He spent three years as a field artillery officer, mostly in Germany, before accepting an early opt-out in 1993.

• He decided to return to school and spent eight years simultaneously earning medical and law degrees from Southern Illinois University. From there it took three years to complete internship and residency requirements at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

• He then spent 13 years with Saint Francis Medical Center in Cape Girardeau, Mo., first as an emergency room physician and for the final 18 months as medical director of emergency services.

• Longing to see the world, he joined the U.S. Department of State as a physician in 2017 and has been stationed in Mexico, the Republic of Djibouti and now Turkey, where he serves as a regional medical officer at the U.S. embassy in Ankara. He expects to be transferred to Paris, France, this summer.

That’s a lot of living packed into 54 years.

And he’s still one of the nicest guys you could ever meet.

“I enjoy what I’m doing, the opportunities I’ve had,” Rothert said.

‘Gives me some stories to tell’

It began in Warsaw, which had suffered through 11 consecutive losing seasons before Rothert joined the lineup as a sophomore during the 1983-84 season. At 6-foot-7, he worked tirelessly to refine his game and become a force inside. He helped carry the Wildcats to three straight regional championships and two trips to the Class A super-sectional.

Despite averaging 19.9 points and 10.4 rebounds per game as a senior, the only bigger colleges that showed interest in his basketball abilities were Army, Air Force and Western Illinois University.

However, armed with a 32 composite score on his ACT, Rothert realized even then that basketball wasn’t his long-term future. Instead, he knew graduating from one of the military academies would eventually give him an upper hand in the job market.

Not that it would be easy.

“Academically, the hard part about it is taking 21 credit hours per semester,” he said of West Point. “You’re so very, very busy trying to take in a lot of information. And then there’s the military stuff, the regimentation. All four years were pretty challenging.

“I was an English literature major and I still had to take calculus and engineering classes. I almost went into physics, but it came down to I really enjoyed coming back (to his room) and reading at night. I picked something I liked. You can read the classics your entire life.”

Rothert became a starter midway through his sophomore season at Army. He averaged 10 points and 5.2 rebounds per game for his career, although he once came close to giving up basketball.

“I was on my way to talk to the coach,” he said. “Somebody outed me. A teammate who knew what I was going to do caught up with me and told me to ‘get in the car.’ So, we did all four years. And I’m happy I did, in retrospect.

“It was a grind playing basketball year-around. I loved being on the court, playing the games. You could still see your name in the paper, but there were still those 21 credit hours. We were always doing homework. And you weren’t dating the cheerleader.”

And then there was facing Robinson, Navy’s 7-1 center who was the No. 1 draft pick of the San Antonio Spurs in 1987 and went on to have a Hall of Fame career. Or trying to guard Simmons, a 6-7 forward at La Salle who was the 1990 national college player of the year and the No. 7 selection by the Sacramento Kings.

“Gives me some stories to tell,” Rothert said. “Those guys hit the athletic Lotto. Let me tell you, when David Robinson steps across the lane, he steps across the lane. You don’t run into players like that in Warsaw and Hamilton.

“I was very proud that I had a decent career in college. When I hung up the shoes, I wasn’t disappointed. I was happy to have the opportunity, happy to move onto the next chapter.”

‘It’s fun to see the different places’

Rothert was expecting to fulfill a five-year military commitment after graduating from West Point.

However, that was shortened to three years with a reserve commitment while he was on active duty. As a lieutenant looking up the chain of command at possible landing spots, he didn’t see himself being career Army, so he took advantage of the opportunity to opt out.

That, of course, meant trying to decide what he wanted to do next. Being a natural overachiever, he chose the grueling path of pursuing law and medical degrees at the same time.

“The business world was not appealing,” he explained. “I have two sisters who are nurses, so I was familiar with medicine. A lot of things about medicine — Medicare inequities, tort reform, liability insurance for doctors — revolve around the law.

“SIU had one of only six programs in the country to combine the two. Of course, it meant I was 35 years old when I got my first serious paycheck.”

He joined Saint Francis Medical Center in Cape Girardeau in 2004. It made sense because his wife, Lorri, is from southern Illinois, so they could be close to family. And it was a good place to raise their five children — four girls and a boy.

However, a friend from West Point who had joined the State Department began sending photos of places he had been across the globe. It piqued Rothert’s interest.

“I always wanted to travel the world, to see things,” he said. “And part of me felt like I didn’t hold up my end of the bargain with the Army (by leaving after three years).

“Our two older girls had gotten into college, so I figured it was now or never. I applied. It took 15 months (to be selected).”

His first stop was in Mexico City. The U.S. has nine consulates in addition to an embassy in Mexico. He spent two years there before being sent to Djibouti, a country in the Horn of Africa bordered by Somaliland to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea to the north and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east.

“I didn’t even know (Djibouti) existed until I joined the foreign service,” Rothert admitted. “It can get to 128 degrees. It’s a completely different world. You don’t want to get sick in those places.”

He has been stationed in Turkey since August 2020. His region also includes Romania, Georgia, the Ukraine and Azerbaijan.

“It’s not at all like my past work in the emergency room,” Rothert said. “Most people (in the military) are pretty healthy.

“There is some clinical practice, but the biggest part of my job is risk management. I assess the capabilities of local health care, so when someone gets sick or injured, I can determine whether they can be taken care of here or should they be airlifted out.”

His wife and their youngest two children have accompanied Rothert to wherever the State Department has sent him. The family spends time learning the history of the countries they travel to, seeing historical sites and soaking in the different cultures.

It’s a long way from growing up along the Mississippi River in Hancock County.

“They call it daddy’s wanderlust,” Rothert said of his children’s reaction to his globe-trotting career choice.

“When we decided to do this, our friends were evenly split — half said it would be great for our kids and half asked how could we do that to our kids. They both were right.”

Rothert will be eligible to retire in nine years. He expects to be stationed in Paris “for a couple of years.” Then, unless he changes his mind, there will be another country, another opportunity, another adventure to pursue.

“I suspect I’ll keep doing it,” he said. “It’s interesting. It’s fun to see the different places. There’s so much stuff to see.

“I was asked once back in high school, ‘OK, you’re in band, chorus, you get really good grades, you’re an all-stater.’ I responded, ‘Yeah, what’s your question?’

“What I should have said is that’s not unusual. Every small school has a group of kids like me. The fact is, being in a place like (Warsaw) puts you in good stead.”

The final paragraph to the column I wrote nearly 36 years ago on Steve Rothert, a small-town high school star about to embark on life’s uncertain journey, remains as true today as it did then.

Leo Durocher was wrong. Nice guys don’t always finish last.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.