Looten’s book ensures QU women’s field hockey program won’t be forgotten footnote

QUINCY — They didn’t want to be relegated to a forgotten footnote in the history of Quincy University athletics.

Thanks to Steve Looten, they won’t.

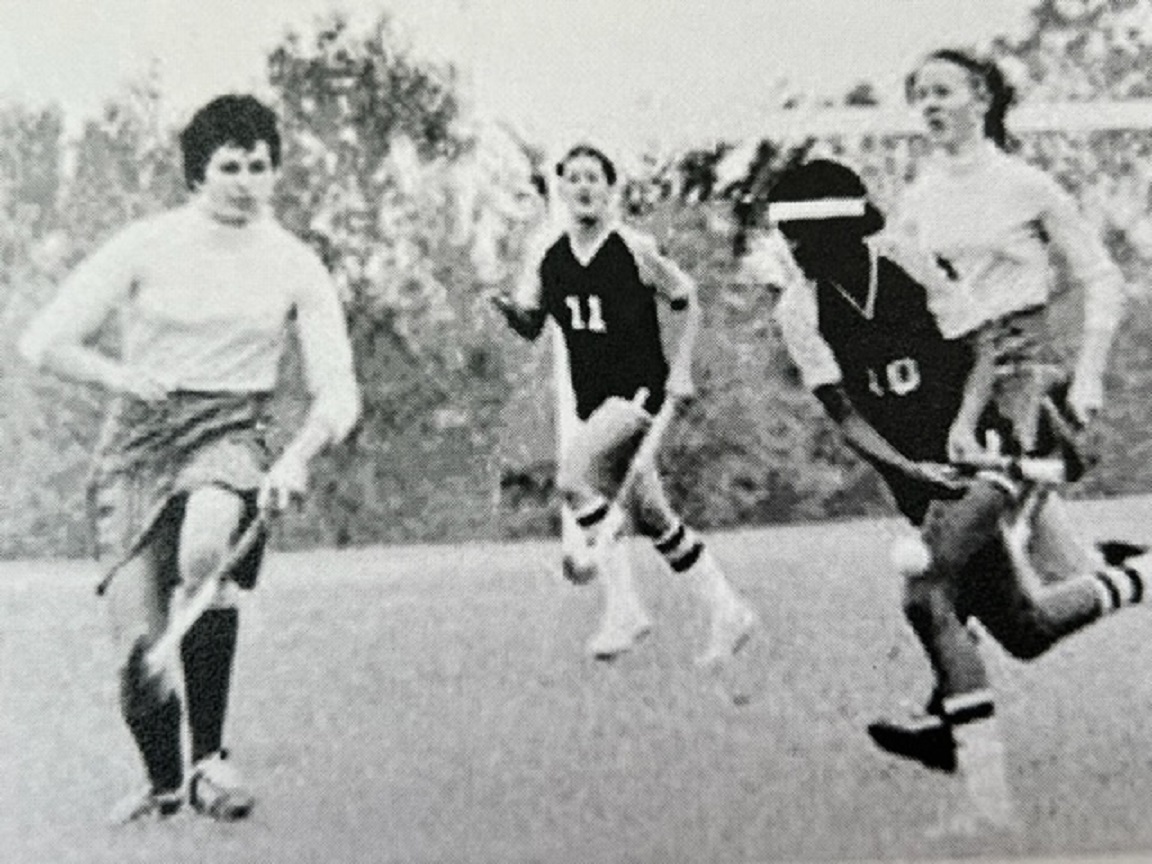

Looten, an acclaimed former sports director for WGEM-TV, has written a book on the QU women’s field hockey program. Although the 127 women who played for QU, then known as Quincy College, during the program’s 12-season run from 1965-76 didn’t realize it at the time, they were trailblazers for women’s athletics at the school.

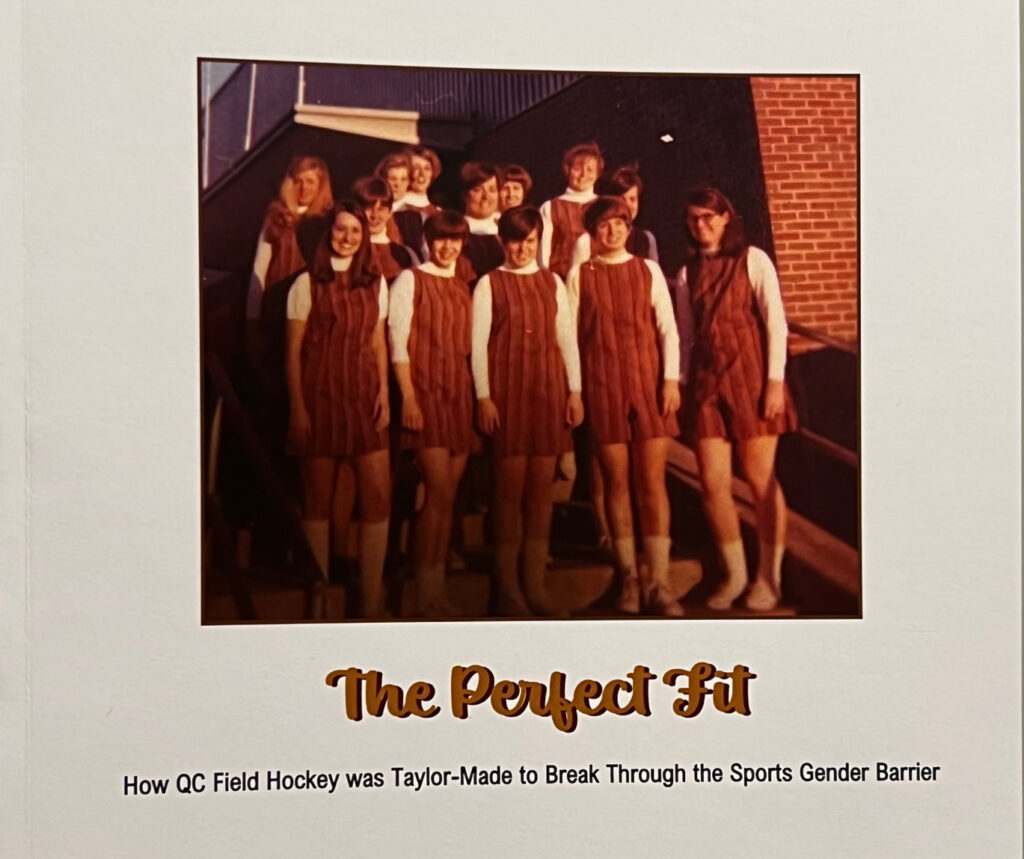

“The Perfect Fit: How QC Field Hockey was Taylor-Made to Break Through the Sports Gender Barrier” is a breezy, 110-page oral history of the little-known and nearly forgotten program. The story is told by players and coaches, many of whom performed when athletic opportunities were not as readily available for women at the high school level, let alone college, as they are today.

The book project began when some former field hockey players, some now in their 70s, approached the QU Hall of Fame Committee, of which Looten is a member, and asked that their contributions be recognized in some way.

“Three different people said they don’t want to be forgotten, that they want their story to be told,” Looten said. “I’ve never seen a field hockey game, I knew none of the players, but after hearing them I told myself, ‘I can do that.’

“I wrote (the book) for them, not for people to buy it. They had no idea at the time they were pioneers, the first women’s sports program in the history of the college. They just wanted to play. I wanted them to be able to tell their story.”

To put the program in historical perspective, it was created 105 years after QU became an institution, 33 years after women were first admitted to the school as full-time day students, and seven years before Congress passed and President Richard Nixon signed legislation known as Title IX.

The number of women participating in athletics at academic institutions on the high school and collegiate levels eventually mushroomed after the passage of Title IX. But in 1965, many of them saw their organized athletic careers end with junior high, with intramurals often being their only athletic outlet at many colleges and universities, especially smaller ones.

(Nationally, Looten wrote, the Women’s Recreation Association made opportunities available for women in intercollegiate sports like field hockey, volleyball, basketball, swimming, archery, tennis, softball and bowling. Not all were universally recognized as college sports, however.)

That was the case at Quincy College when Sharlene Taylor Peter arrived in 1965 to teach physical education, a year after she graduated from Eastern Michigan University, where she had played field hockey for four seasons.

At the time, QC was one of only four Catholic universities in the country to offer a physical education major for women, Looten wrote, so the school drew students from Catholic high schools in Chicago and St. Louis. Many of them were hoping to pursue careers as teachers and coaches.

QC also had a strong intramural program, but only men’s intercollegiate sports were recognized and funded by the administration.

“I decided we were going to have field hockey and then figure out how we were going to do it and where we were going to do it,” Peter, now retired and living in Florida, told Looten.

“When I gathered the (physical education) majors and asked if anybody had ever heard of field hockey, I believe either Colleen Sullivan or Trish Male raised their hand; one or the other, but not both. The next day, 20 or so PE majors showed up on the (intramural) field.

“They were part of a movement without being aware of the movement, hence the birth of intercollegiate sports (for women) at Quincy College.”

The book is filled with stories from players on how they were recruited to play a sport many had never heard of by friends and roommates, of piling into station wagons and sedans to drive to road games, of paying for meals at Burger Chef or grabbing a sack lunch from the school’s cafeteria for a road trip.

They reminisce about getting to practice early to paw through a box of old shin guards hoping to find a pair that didn’t have knots under the instep, of playing on the soccer team’s rough and muddy practice field that often made dribbling the ball difficult, of wearing awful-looking uniforms and of practicing during the dinner hour because, with limited facilities, that was the time allotted.

“We could either practice or eat, take your pick,” recounted Jean Hoban Field, who went on to win 855 volleyball games and three state championships as coach of Immaculate Conception High School in Elmhurst — sixth-best on the Illinois all-time victory list.

“I ended up being a goalie because I didn’t like doing the running that much. I remember the equipment was some kind of goalie pants and a baseball chest protector, and that was it. No glove, no helmet. Who in their right mind does something like that?”

But the sport left a lasting impression on her, as well as other players.

“If I hadn’t played at QC, I probably wouldn’t have coached,” Field admitted.

Jessie Haney Harris, a Chicago native, will be the first field hockey player to be inducted into QU’s Hall of Fame for on-field accomplishments this weekend. She was recruited to play by a friend and went on to score a record 26 goals during her four-year career, which coincided with the final four seasons of the program.

To put that in perspective, the Hawkettes, as they were called, scored only 75 goals in a dozen years.

“She was the Babe Ruth of the program,” Looten said.

“I played hockey on skates on the streets (growing up), and on the playground we played just running,” Harris said in the book. “I just didn’t know about field hockey itself. The sport, the stick, the ball … I didn’t know about any of that.”

One thing Looten found remarkable during his research was the players — his interviews covered all 12 teams, as well as athletes from other sports in later years — didn’t lament that they didn’t have the same amenities as the men’s athletic teams.

“They were just so thankful that they played,” Looten said. “Many of them as kids would go to the playground to play, they would play in junior high, and then there would be no teams when they got to high school.

“Their attitude was unbelievable. These girls were not recruited to be on any team. They were coming for an education, and they got it.”

Trish Highland, for one, went on to have a 30-year career in education and became the first woman to serve as an athletic director at a Class 6A school in Florida.

She was inducted into the Special Olympics of Florida State Hall of Fame in 2008, received the National Federation of State High School Athletic Association’s Outstanding Service Award in 2014 and earned the Women in Sports Leadership Award from the Orlando Sports Commission in 2021.

“Field hockey was a way to channel my need for competition and to play,” Highland told Looten. “… In my mind I was a college athlete representing Quincy College in an intercollegiate event.”

The field hockey team won only two of eight games its first four seasons and posted a 15-37-11 record during its 12-year existence, often playing larger schools from urban areas where the sport was most popular. But it planted a seed.

QC added women’s basketball and tennis as intercollegiate sports the following school year, volleyball in 1968 and softball in 1971 Coincidentally, the school’s enrollment grew from 805 students in 1963-64 to more than 2,000 by 1970-71.

Impressively, QC won the NAIA national softball championship in 1985, one year after finishing second and two decades after first introducing women’s sports.

“Sharlene was the true superstar of this whole thing,” Looten said. “Nothing happens without Sharlene. She believed that field hockey was a great team-building sport to start with because the players had to be physical and athletic.

“The school eventually would have offered the other sports, but she sped up everything by a decade. Players said they later realized Sharlene knew women’s sports were going to grow, and she was getting them ready for something that was not there yet.”

Peter also initiated the women’s softball, basketball and volleyball programs at QC. She left after coaching the softball team to the national title in 1985 for athletic administrative positions at Wisconsin-LaCrosse and Eastern Connecticut State before returning to Quincy in 2002 to coach softball for three years.

She remembers Father Gabriel Brinkman, then the school’s president, once kiddingly accused her of sneaking women’s athletics into Quincy College.

“Guilty as charged,” she replied.

“I was persistent. I think early on (Athletic Director) John (Ortwerth) and probably Father Gabriel realized I was not going to back away. I was going to keep coming with more ideas and more things we ought to do.”

As a result, Quincy University now offers 12 intercollegiate sports for women.

It all started with field hockey, a story that is finally being told.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.