‘The minute they take him away, you’re scared as hell’: Cranial surgery as infant doesn’t keep QND’s Lavery from game he loves

QUINCY — Calvin Lavery didn’t realize the mistake soon enough.

Having walked into a styling center for a haircut, he requested the stylist use an electric razor guard that would take off enough for a stylish look but not too much that he appeared to have shaved his head.

The wrong guard was applied, and the hair quickly fell by the wayside.

“She messed up my haircut,” Lavery lamented.

The stylist also exposed a scar stretching from ear-to-ear across the top of his head.

“Honestly, it was the first time I’d seen the entire thing,” Lavery said. “I’d seen parts of it when I’d comb my hair and things like that, but no one had seen the entire scar.”

Now everyone he encountered at Quincy Notre Dame was bound to notice.

“That was a little humbling,” said Lavery’s mother, Carrie. “Because nobody knew he even had it.”

His friends were understandably inquisitive.

“They were like, ‘What’s that?’” Calvin said. “I had to explain it like 300 times. No one was like, ‘Man, that’s weird.’ They understood. It’s nothing you can change.”

And nothing he worries about these days.

Now the starting quarterback for the playoff-bound QND football team, Lavery is two years removed from the hair-shaving incident. He feels like a lifetime removed from the surgery he underwent when he was just 10 months old to fix the cranial deformity discovered at his birth.

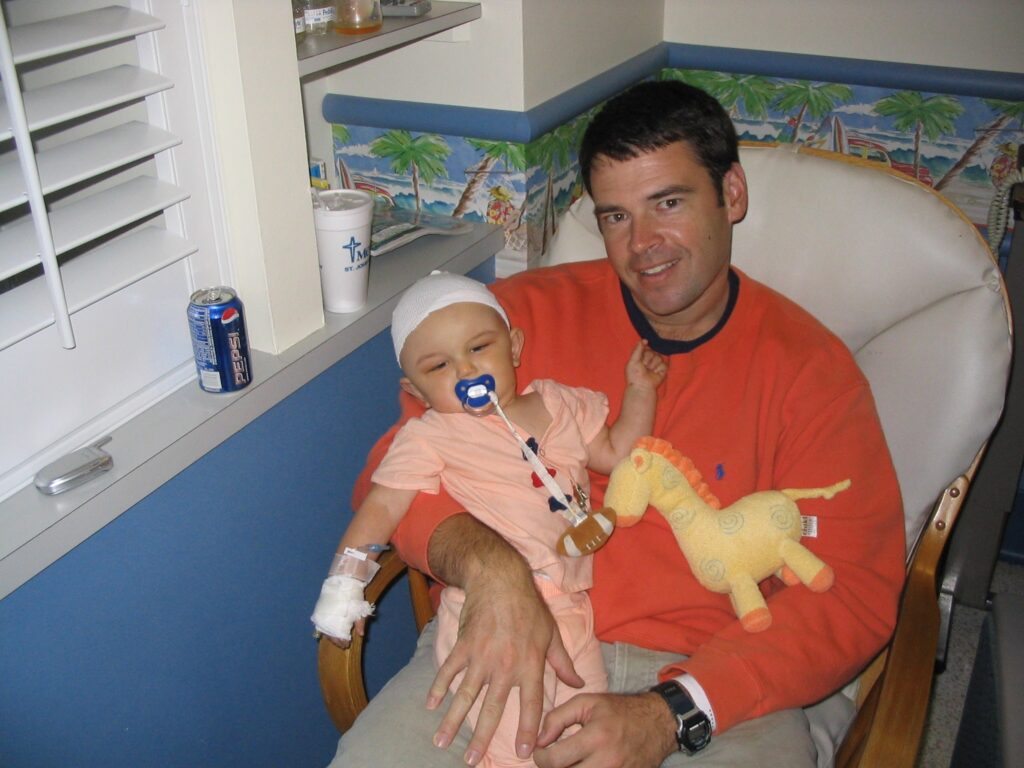

Other than the physical reminders of what he endured — the scar and the bumps on his forehead where the bone grew over the screws — Lavery has no recollection of what those days were like and how harrowing it was for his parents to watch their first-born son undergo life-altering surgery.

“When I started becoming conscious of who I am and how I was raised, I realized I don’t remember any of that,” Calvin said.

It’s a memory his family can’t forget.

‘Is this going to happen? Is everything normal?’

Born Dec. 12, 2003, the first of John and Carrie Lavery’s three kids, Calvin was diagnosed with metopic craniosynostosis. The birth defect occurs when the metopic suture in the skull fuses prematurely, leading to a triangular shape of the head. This condition can limit the room for a baby’s brain to grow and cause developmental delays.

A ridge on Calvin’s forehead was the initial sign something was amiss.

“(Doctors) diagnosed it immediately, but from there, we had conflicting opinions on whether something needed to be done or not,” Carrie said.

The Laverys consulted with doctors at the University of Iowa and Mercy Hospital in St. Louis to learn more about the possibility of cognitive and developmental issues associated with the cranial deformity and how to proceed.

“They have a team of clinicians who look at these kids and figure out if there is some genetic syndrome along with it or is it just a physical abnormality,” Carrie said.

Calvin had no other genetic issues, which paved the way for surgery when he was 10 months old.

“The reason we decided we’re doing this is they tell you there’s a higher percentage risk he could have developmental or mental delays or disabilities because the brain could not develop properly,” Carrie said. “At that point, we said there is no choice.”

The encouragement and support of another Quincy family who had been through a similar situation helped.

Todd and Liz Willing’s son, Zach, was born with a cranial deformity. They met with the Laverys, offering advice and answers to a myriad of questions. They shared photos and stories. They were the perfect sounding board for a young couple trying to make the right decision.

“They came to us and said, ‘Do it,’” Carrie said. “It was very comforting to know they had been through it, and they came through it.”

Zach Willing is the reigning Quincy men’s city singles tennis champion and a sophomore on the Quincy University tennis team. He enjoyed a prosperous high school athletic career much the way Calvin Lavery is these days.

“When your child is born, you have it in your head they’re going to be this,” John Lavery said. “Whether it’s an athlete, whether it’s a professional, then something like this happens and it draws in the question, ‘Is this going to happen? Is everything normal?’”

During a four-surgery, that answer was unclear.

‘You believe and you have the faith to carry you through it’

Dr. Jeffrey Marsh performed fronto-oribital advancement surgery at Mercy Hospital when Calvin was 10 months old. The surgery requires an incision to be made from ear-to-ear. The bones of the forehead and a strip of bone from the upper orbital rim are separated from the skull, then advanced forward and remodeled.

In essence, they saw the baby’s head open, peel back the bones down to the eye socket and then put the puzzle back together again.

John Lavery described it as taking a hard-boiled egg, crushing the shell and reforming it.

“I had total confidence in where we were at, the surgeons, the number of times they had done it,” John said. “We checked it out. We were really comfortable we were in the right place.”

They also had the right surgeon. Marsh served as the director of pediatric plastic surgery at Mercy Hospital and the head of Mercy’s Cleft Lip/Palate and Craniofacial Deformities Center. He also traveled to Asia and other locales to teach physicians the skills needed to treat deformities in babies.

“He’s world renowned,” Carrie said.

Knowing that doesn’t alter the emotions the day of the surgery.

“It was brutal,” Carrie described it. “Just sitting in the waiting room waiting.”

Yet at every turn, angels were offering support.

“We had friends come down from Chicago to sit with us,” Carrie said. “A nurse gave us a prayer medal. The neurosurgeon looks at you and says, ‘I’m going to protect his head and nothing happens to him.’ You believe and you have the faith to carry you through it. But it’s scary.”

No amount of support changes that.

“The minute they take him away, you’re scared as hell,” John said.

Nothing prepares anyone for that.

“It’s just the two of us,” Carrie said. “And the tears are just flowing.”

Both sets of grandparents kept them company at the hospital along, with a myriad of support from afar. However, the Laverys’ wait wasn’t over once the surgery was done. Calvin spent the following four days in the pediatric ICU with his eyes swollen shut for the first three days.

They knew all would be OK on the fourth day.

“The day he opened his eyes just a little crack, Cal made some little funny noise with his mouth,” Carrie said. “I look over and (grandfather Mike Lavery) just started bawling. You knew he was going to be all right.”

Still, more hurdles remained.

‘He is hard-headed in more than one way’

Before being discharged from the hospital, Calvin was fitted for a protective helmet. The surgery left a gap of bone behind the incision that needed to naturally grow and harden over time. In the meantime, it needed to be protected.

It resulted in an adorable first Halloween costume as his parents dressed him as a football player, complete with the helmet and an Emmitt Smith No. 22 Dallas Cowboys jersey.

Yet it also had the Laverys concerned with everything Calvin did.

“You don’t want him in day care. You just want to protect him,” Carrie said. “Then you also realize, day by day, he gets better.”

The bones began to fuse, and the head started to harden. After six months, Calvin no longer was required to wear the protective helmet. Annual follow-up visits to Mercy Hospital came with clean bills of health.

The real moment when everyone knew the surgery and the worry were a thing of the past came when he was about 3 years old. Calvin was running through the house when he tripped and fell.

“He smashes his head into the wall and dents the drywall,” John said. “Literally, we had to repair the drywall. I was like, ‘His head’s hard.’”

He’s been hard-headed ever since.

“He is hard-headed in more than one way,” Carrie said with a laugh.

His coaches would call it determined.

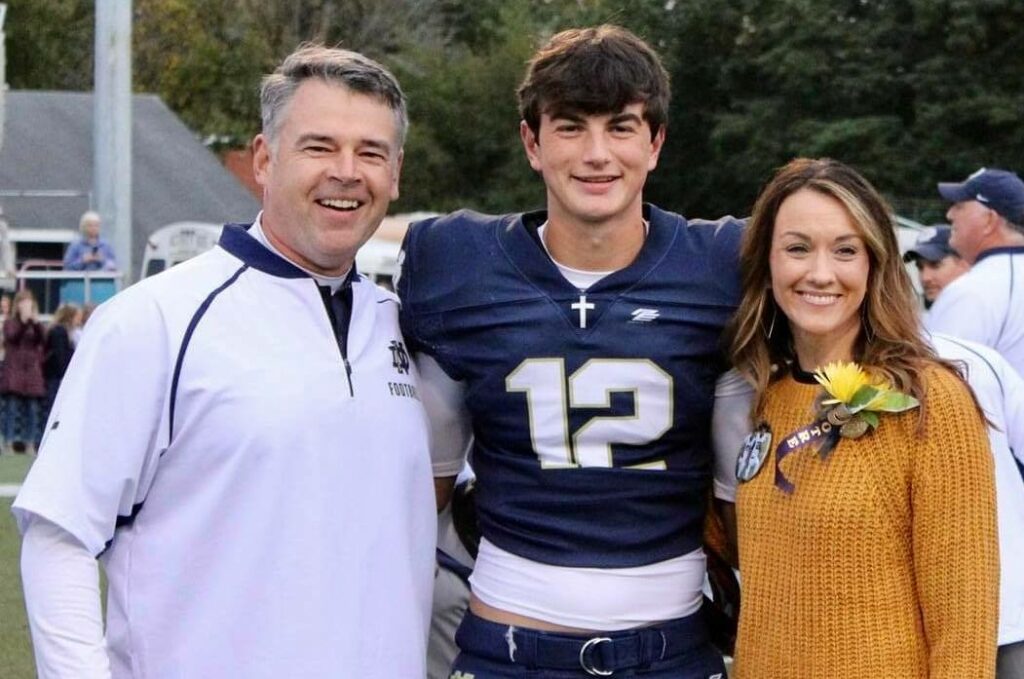

Lavery has started each of the Raiders’ nine games this season, leading them to a 6-3 record while completing 114 passes for 1,163 yards and throwing nine touchdowns. He’s also scored three rushing touchdowns.

He hasn’t been afraid to stick his head in on a play requiring a collision or extreme contact, which can be unnerving for his parents.

“A little bit,” Carrie said. “When it’s your own kid, you’re like, ‘Get up. You’re fine.’”

Every time, Calvin has popped right back up.

“I don’t ever think about it,” he said. “I play with no regrets.”

He plays knowing his head is as hard as a rock.

“I like to think sometimes my head is metal,” Calvin said. “I have plates and screws in there. My head is stronger than everyone else’s.”

There is no reason to hold back.

“I look at where it all started and not knowing where life is going to take you,” Carrie said. “I think about the joy I see in him that he gets to do this everyday. And we say, ‘Don’t take anything for granted. You don’t know what tomorrow is going to bring. Work hard and enjoy it every day.’

“It’s been a gift to sit (in the stands) and watch. Sometimes you cringe, and you don’t really like it when there’s three guys on top of him. As a mom, that’s not a view I want to look at. But I also know he’s loving what he’s doing.”

It’s what he’s always wanted to do.

“Ever since fourth grade, I’ve been on the Notre Dame sideline,” Calvin said. “I’ve been a ballboy and a waterboy. I’ve been around it for a while. It’s been my life dream to be out there on the field making plays.”

To make it complete, his father is on the sideline as an offensive assistant coach.

“I know I’m privileged to get an inside look every day,” John said.

It’s made the story complete.

The Laverys can look at the pictures taken in the hospital with Calvin’s eyes swollen shut and then flip to the picture taken on senior night before he led the dismantling of Granite City and know everything has come full circle. A bright future comes with that.

“I always get emotional,” John said. “You can’t help but be emotional seeing the young man he’s become. It makes you proud and it makes you thankful.”

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.